How I Negotiate

These are some practices I follow in my negotiations:

• Bounded loss: Be clear about the worst-case scenario, and ask yourself if you’re okay with it. I’m okay taking a bounded loss, such as losing one month’s fees in an exceptional situation. But not an unbounded loss. Say a startup approached me to fix their systems, for a fee of $30,000. Should I say yes? Achieving the goal may require me to rebuild their entire tech, which can be a hundred thousand dollars worth of work. If I’m charging only $30,000, I’ve lost $70,000. If it turns out to cost $1,000,000, I’ve lost $930,000. In this situation, there’s no limit to how much I can lose. It’s an unbounded loss. Which I won’t agree to. The problem here isn’t that there’s risk — there’s a certain amount of risk everywhere, and obsessing about avoiding any risk at all holds you back. It’s okay to take a risk, as long as a) you know the worst-case scenario and b) are okay with it. Don’t take on unbounded risks.

• When you mention a fee, the negotiation becomes about that fee: If you’re offering the choice of an hourly billing model where the fee will be the hourly rate x number of hours worked which can’t be predicted in advance and an outcome billing model where you charge a fixed fee to deliver the outcomes independent of the hours spent, don’t mention prices, even if they’re illustrative or examples, because the conversation becomes about that number. If they say no, does it mean they’re not okay with the model or okay with the model but not the number? Both sides will be confused when you try to negotiate two things at once. So negotiate one thing at once. Just ask the question at an abstract level. If they respond strongly, “Oh, no, we hired someone in the hourly model earlier and we received a huge, unpredictable bill, so we don’t want that at all. We need to know ahead of time what the cost is going to be”, then you got clarity on what works for the client which you may not have got had you muddled the conversation by bringing in the numbers.

• Barter: Be clear about things that are valuable to you, but which you’d give up in exchange for something else that’s valuable.

In the days before online ordering, I used to order a single dish from a nearby restaurant by phone. They’d balk saying that it’s below the minimum amount they deliver. I asked them to charge me more, which they did, but they’d still object. I then asked them to charge me a delivery fee, but they’d still object. Eventually they refused to deliver, so I stopped ordering from them, causing them to lose business. As the book Getting To Yes explains, when we take a position in a negotiation (“We require a minimum order amount”), we have an underlying interest (“We don’t want to lose money delivering small orders”). We should not give up our interest, but we should be flexible on the way we get there (such as by accepting a delivery fee, or a higher price for the dish).

As a consultant, I want to be mentally flexible to meet customers where they are, to win more business. So, don’t say “no” if you can instead say “Yes, I can do that, but in that case, I’ll have to increase my fee.” “No”, for some reason, puts people in argument mode, where they turn off their brain and mindlessly keep repeating, “I want this! I want this! I want this!”. Instead saying, “Yes, I can do that, but in exchange…” shuts them up.

• Don’t ask for unreasonable things, things you wouldn’t agree to if you were in their shoes. Also be clear what don’t have value to you, and don’t even ask for those in the first place. For example, I’m not going to sue my clients even if they don’t pay, so I removed clauses from my contract that enable me to sue them, and are offensive rather than defensive.

Some people suggest asking for things that are not a priority, only to let them go later in the negotiation, as a trick. But tricks can make you win the battle and lose the war, as I found: First, it prolongs the negotiation for weeks. Second, I’ve seen a client who was trusting of me see these unfair clauses and become distrusting, examining every clause with a fine-toothed comb to ensure I'm not taking advantage of them. That's a bad start to a relationship. We want a relationship of trust, not one where each side has to look over their shoulder to ensure that the other side isn’t taking advantage of them. Third, even if we tell ourselves that we’re going to let go of a particular clause, at a psychological level, I have once become attached to my position, dug in my heels and made it a battle of wits. All of us have these psychological biases. Solve all these problems by not asking for what you wouldn’t agree to. It’s also in compliance with the golden rule, and so an honorable (business) practice.

• Quote the minimum that works for you, below which you’d walk away. For example, if you’d like to quote $400/hour but would also accept $300, quote $300 and make it final. Why? First, not everyone will negotiate — some will walk away. Apply Jeff Bezos’s regret minimisation framework and pick the option you’d regret less if it didn’t work out. Would you regret it more if you quoted 400 and got nothing, or quoted and got 300? Second, quoting the minimum leads to streamlined negotiations, rather than ones that get bogged down for a month or two as both sides negotiate each point endlesslessly. When you quote the minimum, you should not permit any negotiation1. If you’re hesitating to say no, maybe you didn’t quote the minimum?

• Positivity: Start the negotiation with positivity and an assumption of trust in the other side’s intentions and competence, and switch to distrust only if the other side takes advantage of you. Don’t start with distrust and make them prove themselves to earn your trust. That’s a bad attitude. After having the misfortune of negotiating with multiple ill-intentioned companies, I unknowingly became distrustful and did not start the next negotiation with a win/win attitude. I lost a deal with a founder who was well-intentioned, because I behaved like a bad guy. So you need to have your own inner sense of what’s right and wrong and, as Steve Jobs put it, not let the noise of other people’s opinions drown out your own inner voice. Have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.

• Completeness: Over the course of the negotiation, make sure you’ve agreed on all relevant aspects. I’ve seen many disputes arise from incomplete agreements and assumptions which, as the saying goes, make an ass of u and me.

• Termination: When negotiating, agree on termination clauses at the outset, when trust is still there. That’s was professionals do. Amateurs avoid these awkward conversations and get into disputes later. You hope the building doesn’t catch fire, but if it does, you need to have a clearly marked fire exit to take, rather than being trapped inside, or trying to look for one through the smoke, which isn’t the right time.

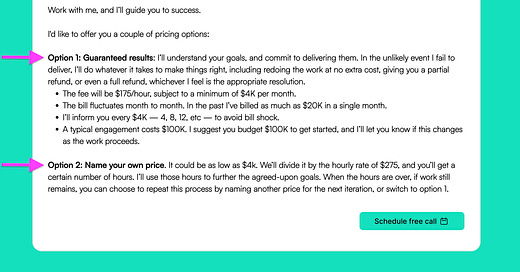

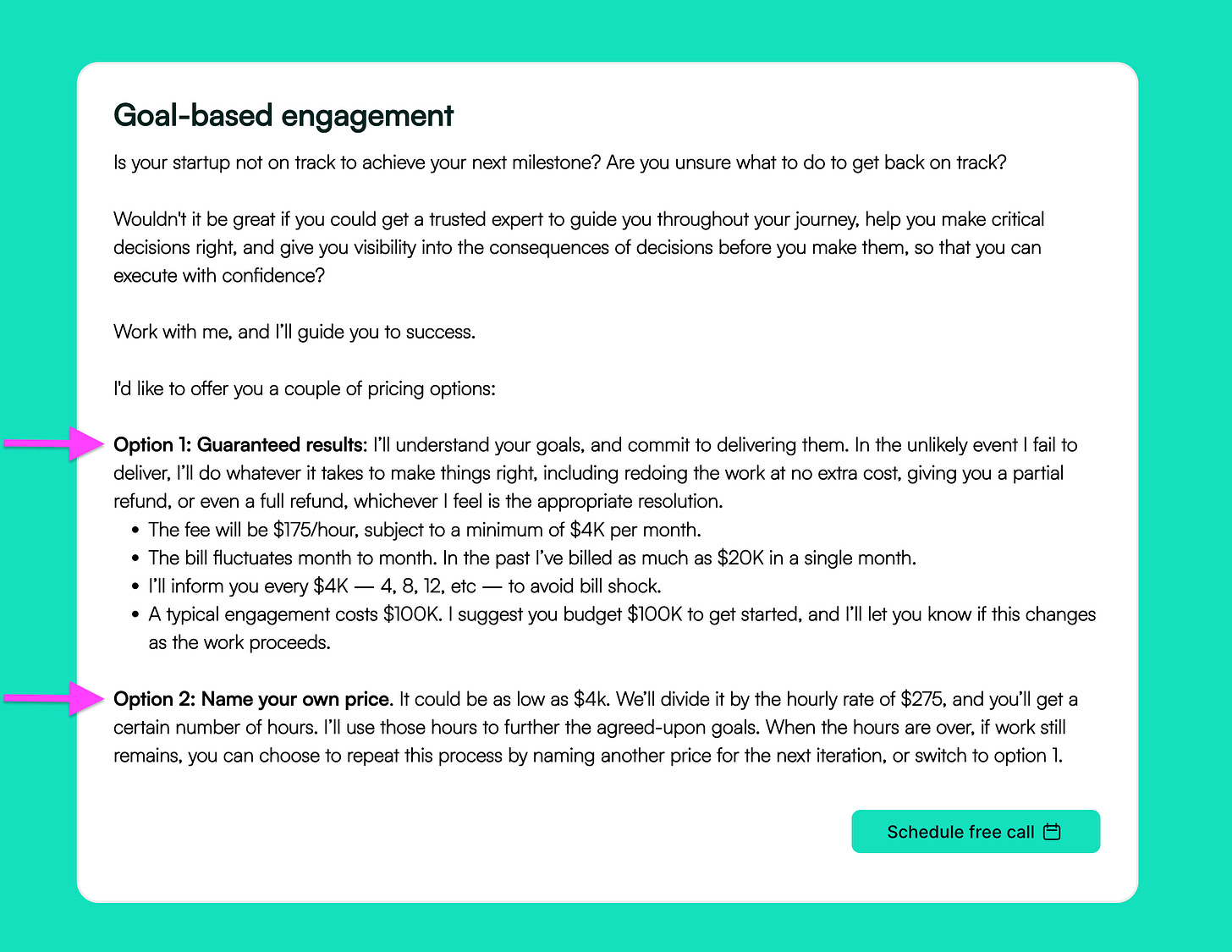

• Offer them some options on the website, like two here:

The negotiation hasn’t really begun until you’ve offered the lead some options. You can ask them a lot of questions and get good answers, and they can find out whatever they want to find out about you. You could spend weeks in this process, enjoying it, feeling that they’re the kind of people you want to work with. This may fool you into thinking you’re making progress in the negotiation. But the process hasn’t really begun until you’ve put a few options on the table. If you do that three weeks in, you’ve chatted for three weeks and only then begun the real negotiation. So get to that point as early as possible, ideally before the first meeting, by mentioning it on the website, and asking them to go through it before the first meeting. If you can’t, message it to them when you’re introduced.

• Be clear about non-negotiables: In every negotiation, there are must-haves: they’re not negotiable, and if the lead insists, you’d rather walk away. Sometimes we begin a negotiation without being clear what our non-negotiables are. This prolongs the negotiation. The other side can sense your doubt and skillfully maneuver you into second-guessing yourself and working against your interests, agreeing to a deal that you later regret. Regardless of the outcome, the process can feel frustrating and draining. To prevent these problems, be clear about your non-negotiables. If you tell yourself “X is non-negotiable”, challenge yourself by asking, “Would I willing to trade X away for something else that’s valuable?” If so, it’s not non-negotiable. Once you know what your non-negotiables are, if and when you talk about them, use black and white language like “must”, “cannot”, “I don’t allow that” or “Then we can’t work together”. Not shades of grey like “Let’s try to” or “It would be good if” — these imply that they’re negotiable, so they’ll argue more. You’re practically inviting them to! A sales conversation is like a metropolis with thousands of roads that can be explored. If the lead walks down certain roads, let him, because it will help you understand his desired outcomes, problems, funding constraints, maturity, and so on. Such diversions are helpful. But others are not — you should shut down such conversations unambiguously, such as by saying “I don’t accept equity”. If they insist saying, “We want to work with people who are committed to the mission and blah blah” Respond with “Then we can’t work together.” Leave no room for discussion. Barricade the roads that you don’t want the lead to walk further down. Otherwise the discussion will be protracted and you’ll feel disrespected and disappointed when they don’t work with you at the end of it all. When I began consulting, I approached conversations with a lot of patience, but most leads misused that patience. So don’t have infinite patience.

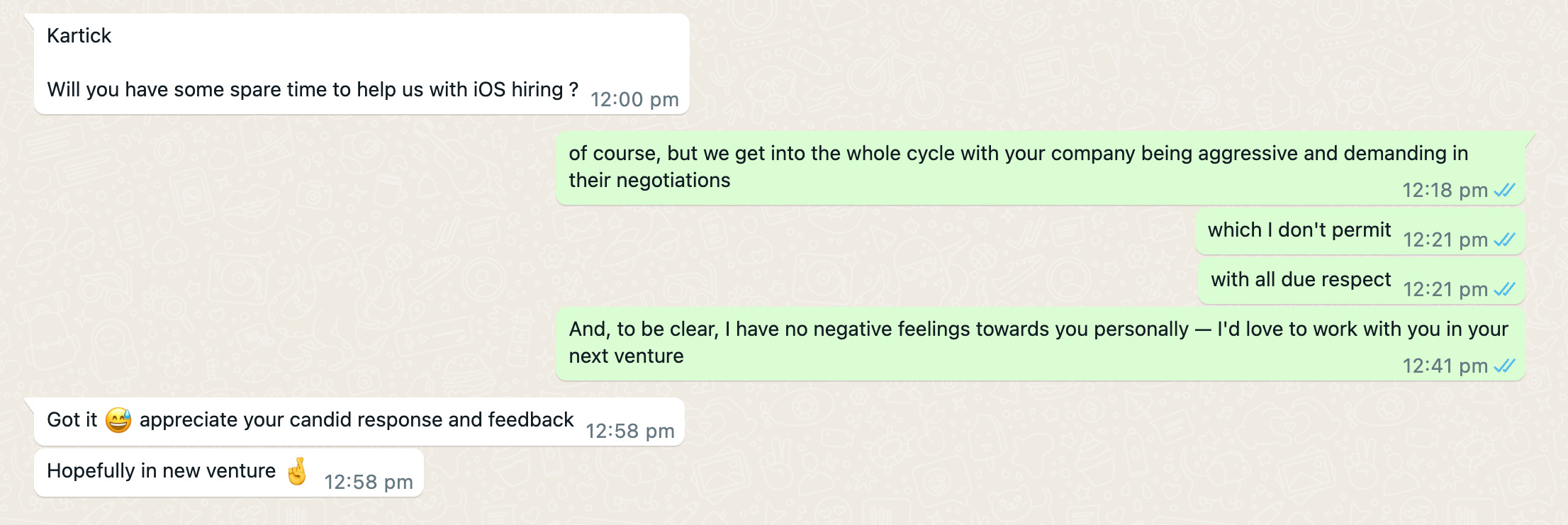

• When they try to trick you, turn the tables on them: Quite a few leads will try tricks such as insisting on an abysmal fee, like 1 lakh rupees for a new car. They do this knowing that it’s unreasonable, expecting you to say no, but in the process agree to a lower number than you would otherwise. The only way to protect yourself from these — and other psychological tricks — is to turn the tables on them. I was discussing with a lead a project that would’ve cost $100K. We got into negotiating the price and after going back and forth a few times, he said, “We’re looking to pay max 10 lakh rupees”. I responded with “Then we should conclude this conversation.” Another cheap trick is demeaning you: one lead told me, “I know lots of qualified people for this job.” The first time someone played this trick on me, and I fell for it, and ended up being afraid to ask for what I wanted. Later, someone told me, “Kartick, that was a trick. If he had someone better than you, why would he be talking to you?” So, the second time I responded, “Then why are you talking to me?” He was speechless. When he is, don’t help him out. Let them stew in it. From your side, embrace the awkwardness. Count to 30 if you have to. Whoever is comfortable with the silence longer wins. When I turned the table on his trick, he didn’t try any more, and conducted the rest of the conversation straightforwardly. Don’t hesitate to punish tricksters.

• Meta-negotiation: Sometimes the negotiation doesn’t proceed well, because of communication or attitude problems. Then you need to stop the conversation and have a negotiation about how to negotiate. For example, one lead rudely dismissed my question and asked one of their own. I answered it. Later in the conversation, I revisited my question, and they didn’t answer. Then I told them, “When I ask you a question, I expect you to answer it.” They didn’t say anything, so I continued, “Is that clear?” They responded saying “We need to keep the conversation moving forward.” I told them, “Yes, and in order to do that, you need to answer my questions. This conversation is not just for you. It’s a 2-way street. When you ask me a question, do you want me to ignore you the way you’ve been ignoring me?” Sometimes you have to stop the actual negotiation and switch to a status negotiation. At this point, the conversation came to an end, which was good, since they’d have been a bad client with a hierarchical attitude that they’re above me and questions for them are a way to assert dominance rather than get information. Don’t hesitate to instruct your leads on how to behave in the conversation2. Either they’ll apologise and things will go well, or they’ll react negatively and reveal their true colors, at which point you can hang up. Both outcomes are better than continuing with ambiguity and concerns.

• If they’re stubborn, ratchet3 up your bluntness. Say you require invoices to be paid in a month. It’s non-negotiable for you, but they ask for a 2 month repayment period. You might respond in a cooperative way that tries to explain your situation and build understanding: “Sorry, that doesn’t work for me, because it creates a cash flow problem for me.” Some people will treat such polite language as a sign of weakness and try to exploit you. In either case, they may come back with, “I understand but we have a policy of 2-month repayment." Then you need to switch from collaborative language to instructional language: “If we’re to work together, invoices will need to be paid in a month.” me.” If they say “no”, counter with “Then we can’t work together”. Remember not to say it with ego, because people can sense it and it will backfire — you won’t get the result you want. Instead, say it in a calm, factual manner. Be 100% on directness and 0% on ego. Adopt the tone of a scientist, who says what he needs to say bluntly but in an ego-less manner. But saying it bluntly is important so that you’re not taken advantage of, and to communicate that this is not a deal between a servant and a master, but between equals.

• Set limits on your negotiation: Before you begin negotiations, you should, in your own mind, set some limits and be clear about the boundaries of what you’ll accept:

The first limit is that the negotiation must conclude by a certain date4, say in 2 months, after which the situation on the ground may change and I’ll have to re-plan the whole engagement. After the deadline, I’ll have to charge for the negotiation itself. That’s a calendar limit.

The second limit I set is a clock limit: if it takes too many hours, even if it’s within 2 months, I tell them we’re overdoing it, and that the offer on the table is the best we can get, and that further negotiation won’t improve it, and that the time has come for them to make a decision one way or the other.

The third kind is bad behavior. Some companies negotiate in a way that damages trust. If that happens, call it out and say that further negotiation will damage trust, even before the engagement starts, at which point it doesn’t even make sense to work together. So we need to stop negotiating and start the engagement. If you feel they’re trying to squeeze as much as possible out of you, say so. Call out the elephant in the room. Again, don’t permit manipulative behavior, behavior that makes you feel taken advantage of. Another behavior is when you’ve negotiated with the key decision-maker. After a process that takes longer than it should, when you feel that you’ve finally reached a conclusion, you’re shunted off to a finance/HR team, who will try to squeeze you more. From now on, when I send an agreement and they ask for some changes, before responding to their comments, I’ll ask them what the process is from their side. What will happen after they agree? Will it go to the finance team? HR team? You shouldn’t remain in the dark as to the plan. If they say yes, I’ll tell them to invite the finance team to negotiate along with them, so that we can get it done faster. If they say no, I’ll say that if after we reach agreement, they reopen the negotiation, I’ll reopen it, too. I might increase my fee. If they disagree, I’ll tell them I won’t participate in a one-sided negotiation.

The fourth limit I set is on prospects who negotiated, did not sign me up, and then returned after a few months or next year. I tell them that since I spent time last time and did not get paid for it, I’ll have to charge them for the negotiation. Or even begin with no:

Sometimes we’re frustrated after the fact, which doesn’t help. Quite a few Indian companies won’t respect your time, or treat you reasonably. So take care of yourself. Have the self-confidence to set your own rules, remembering that you’re an equal, not a supplicant. Learn from auto drivers who, if you negotiate too long, just drive away.

• Don’t hesitate to instruct: Set a minimum bar for behavior you expect from the other side, and if they fall short, instruct them, “You need to…” For example, “When I say something, you need to listen with an open mind. Leave aside your opinion. Think about what I’ve said. If you can’t think on the spot, tell me you’ll think about it and get back later. Is that clear?” Ask the “Is that clear?” in a tone of instructing them, the way a boss would instruct his subordinate. If they still don’t get it, don’t hesitate to say, “I work only with open-minded people. You’ve been closed-minded. Do you want to switch to an open mind from now on, or should we part ways?”

Except in exchange for fewer outcomes or slower delivery.

Don’t discount if the client feels great to work with: I had founders from a developed country, one of whom was playing a key role in a $500m business. They were intelligent and articulate, able to understand and align with what I was saying quickly. They didn’t argue unnecessarily. We made progress faster than with some of my other leads. They respected what I bring to the table as a tech advisor to CXOs. Their side business generates $2m a year, so they had the ability to pay. Since both the willingness to pay and ability to pay were taken care of, I was confident that they’d pay me the reasonable fee I’d quoted, which was also significantly less than what someone in their country would charge. But I found to my shock that they wanted to pay me a mid-level engineer’s salary while still expecting a full-time CTO’s work. It turned out that they were very financially disciplined. They’re the kind of people who’d have a daily budget and if that got exhausted, skip dinner. They were hard-nosed when it comes to money, decoupling that from the relationship, so I should do the same going forward.

Having said that, if you do want to negotiate on price without getting anything in exchange, here are two tips:

Don’t negotiate against yourself: If you’ve quoted a price, and they say no, ask them to quote a price.

Have only one round of negotiation: Tell them to tell you the highest they’re willing to pay, and you’re going to say say yes or no, and we’re not going negotiate the way we do when we buy vegetables on the road side: 100. 50. 80. 70. 75. If they strike you as petty, tell them they have only one chance at this negotiation.

A different scenario is when they ask for a minor reduction in price, like 9K instead of 10K. Respond to that with, “If you can afford 9, you can also afford 10.”

I used to hesitate thinking that these are founders and CEOs and so it would not be right to instruct them in the basics. I’ve now let go of that reservation. If they were so good, they’d have conducted the negotiation well and we wouldn’t have been in this place, to begin with. People who aren’t competent don’t have a right to get offended when educated. If they do, I hang up.

Don’t go from 0-100 at one go; that would be rude on your part.

On the other hand, some people are stuck at 20 and can’t escalate when necessary.

Neither is right. Instead, start polite and keep ratcheting up a step at a time.

Be clear with yourself that discounts are time-bound. If they fail to meet the deadline, revoke the discount.