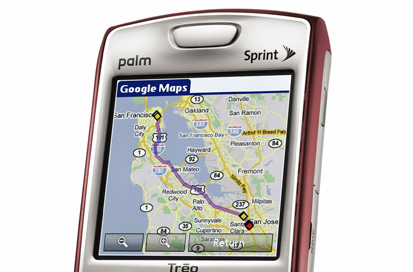

I started working in mobile in 2008. I built apps for various phones like Nokia, Sony Ericsson, LG, Windows Mobile and BlackBerry. These came in different form factors like candybar:

flip:

and slider:

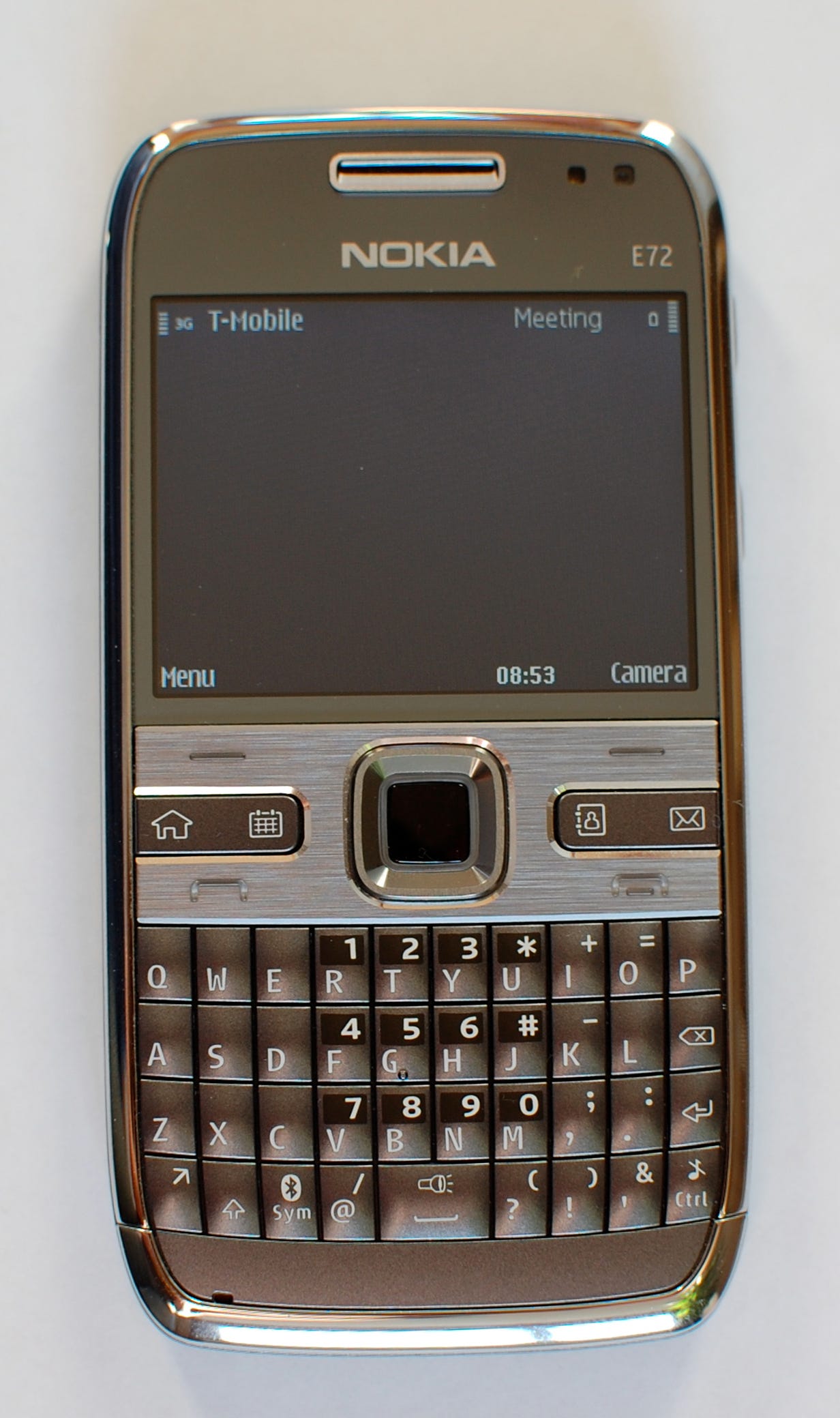

Some had a full QWERTY keyboard:

Some had a landscape screen, like computers, and unlike mobile phones of the day:

QWERTY or not, all of them had keypads for text input. The concept of using a touchscreen for input didn’t exist yet — keypads were separate hardware, like the keyboard on your computer.

The equivalent of a mouse was a D-pad:

This consisted of a central button which worked like a mouse click, along with buttons on four sides to move in all four directions 1.

An alternative was a joystick, which served the same purpose, except that it physically moved in all four directions, instead of having four buttons on four sides:

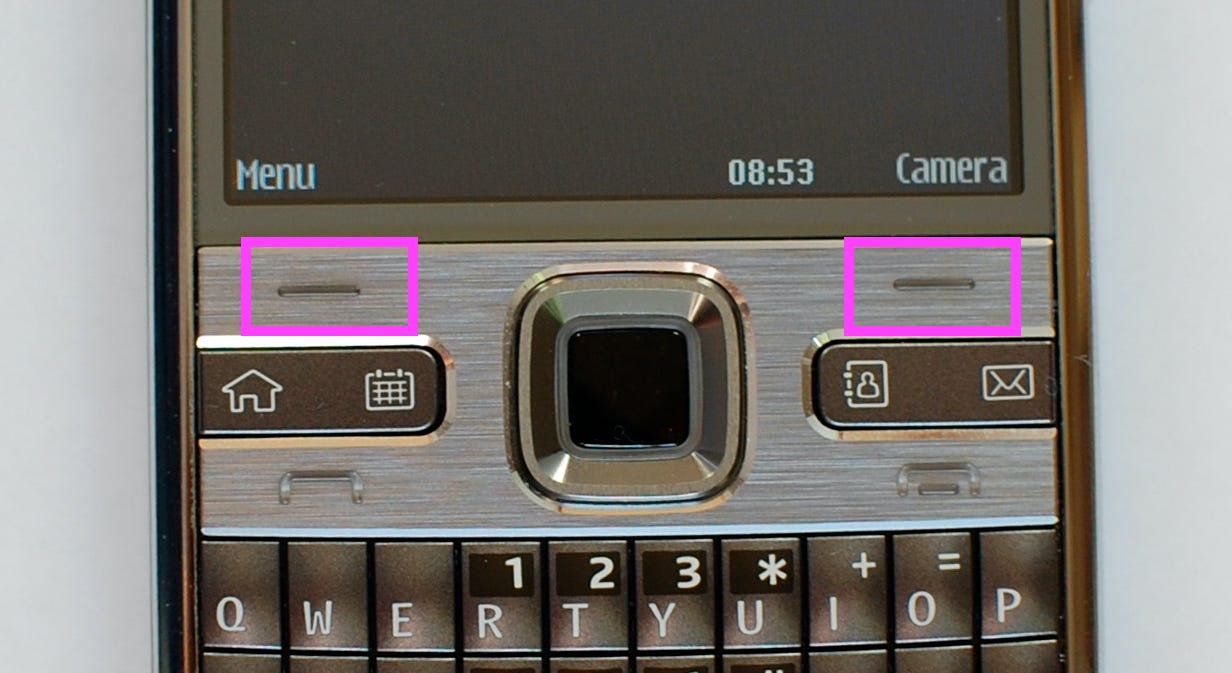

In addition, we had soft keys:

These were hardware buttons that performed the action shown immediately above them onscreen.

The overall experience of using apps was abysmal, on all these phones. The UX was bad, capabilities were limited, and there was so much friction, to the point where I never bothered to use apps on phone, not even the ones I built. Apps and the Internet belonged on the desktop, and the phone was for calls and SMSs. Apps on the phone were an edge case for some very dedicated or weird people, like living in a campervan rather than a house.

At this point, the iPhone was released, but it didn’t really change anything yet. There was a lot of promise and excitement, but it was so radically different that no one knew what to make of it. Was it the future? Some people felt so. Some felt it’s only a bold and innovative experiment, and will succeed in a niche, but no more. Some people posited a low end / high end split, with the old Nokias being the low end and the iPhone being the high, with both continuing in their segment of the market, just as we have mass-market and luxury cars, neither displacing the other. Some felt that it didn’t matter how good smartphones are as long as they’re priced 10x more than the phones most people bought and are willing to pay for.

Some legacy platforms like Symbian added touch. Some people agreed with this choice —they said the way forward is to add touch and other modern features to traditional phones, rather than throwing them out completely and redesigning from scratch.

Intel built a new operating system called Moblin. Some people felt that Intel, being at the heart of the computer industry, will succeed. Microsoft made Windows Phone 7. I thought it had a real chance, since was a polished platform. Others disagreed, saying it’s not Windows if it doesn’t have compatibility with Win32 apps, so the strengths of Windows don’t carry over to Windows Phone, and that the Microsoft brand name means nothing.

Even people who agreed on the eventual outcome — we’ll all be using iPhone-like phones — disagreed on how fast we’ll get there.

Looking back, it’s interesting to evaluate my own predictions:

I felt we’ll all be using iPhones. (Turned out to be partly right. The part that I got right is that we’re using iPhone-like phones, with apps, a modern operating system, fluid animated interfaces living on giant touchscreens, and few hardware buttons. The part I got wrong is that most people use an iPhone clone, in the form of Android.)

I felt that the old platforms like Symbian are dead, that you can’t bolt on the UX of the future onto the tech of the past, any more than you can put lipstick on a pig. You need to build the platform up from scratch. There’s no transition path for these pigs. (Turned out to be right.)

The transition will happen fast. (Right.)

That’s how living through a transition is. Nobody knows how it will play out. All kinds of experiments are being conducted at once, by old and new players. There’s excitement 2. All the old norms are out of the window.

If you weren’t around for the smartphone transition, you would not understand this, because things have settled down. “How else can it be?” you may wonder. Kids of 2100 may ask, “Of course we vacation on the moon — how else can it be?”

Things always seem clear in retrospect, just as they do at the end of a movie. But when you’re watching the movie, you don’t know how it will play out. In fact, that’s what makes movies exciting. What could be more exciting than a movie? Living through it in real life!

Clay Shirky wrote eloquently about transitions:

Elizabeth Eisenstein’s magisterial treatment of Gutenberg’s invention, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, opens with a recounting of her research into the early history of the printing press. She was able to find many descriptions of life in the early 1400s, the era before movable type. Literacy was limited, the Catholic Church was the pan-European political force, Mass was in Latin, and the average book was the Bible. She was also able to find endless descriptions of life in the late 1500s, after Gutenberg’s invention had started to spread. Literacy was on the rise, as were books written in contemporary languages, Copernicus had published his epochal work on astronomy, and Martin Luther’s use of the press to reform the Church was upending both religious and political stability.

What Eisenstein focused on, though, was how many historians ignored the effects of the press circa 1500. To describe life before or after the spread of print was child’s play; those dates were safely distanced from upheaval. The hard question Eisenstein’s book asks is “How did we get from the world before the printing press to the world after it? What was the revolution itself like?”

Chaotic, as it turns out. The Bible was translated into local languages; was this an educational boon or the work of the devil? Erotic novels appeared, prompting the same set of questions. Copies of Aristotle and Galen circulated widely, but direct encounter with the relevant texts revealed that the two sources clashed, tarnishing faith in the Ancients. As novelty spread, old institutions seemed exhausted while new ones seemed untrustworthy; as a result, people almost literally didn’t know what to think. If you can’t trust Aristotle, who can you trust?

During the wrenching transition to print, experiments were only revealed in retrospect to be turning points. Aldus Manutius, the Venetian printer and publisher, invented the smaller octavo volume along with italic type. What seemed like a minor change — take a book and shrink it — was in retrospect a key innovation in the democratization of the printed word, as books became cheaper, more portable, and therefore more desirable, expanding the market for all publishers, which heightened the value of literacy still further.

That is what real revolutions are like. The old stuff gets broken faster than the new stuff is put in its place. The importance of any given experiment isn’t apparent at the moment it appears; big changes stall, small changes spread. Even the revolutionaries can’t predict what will happen.

Of course, the revolution will soon come to an end. Norms will evolve: every phone today has a giant screen, an animated interface, touch-first UI, a powerful OS, limited hardware buttons and apps. People’s tolerance for experimentation will reduce drastically. The market will settle down into fewer players. Life will become routine.

But when you’re living through the revolution, all kinds of ideas, incremental and crazy, are being tried out, we don’t know how it will all work out, and we’re enjoying the ride, not knowing what comes next!

Some had eight buttons: pressing in the corner let you go top-left at one go, rather than having to left first and then up.

Uncertainty if you’re conservative.